Ed Viesturs: The Greatest American Climber in History

Edmund “Ed” Viesturs was born on June 22, 1959, in a world where few could imagine the heights he would one day reach. Growing up as a high school student in Illinois, Viesturs discovered rock climbing, and this simple introduction would set the course for one of the most remarkable mountaineering careers in American history.

After graduating high school in 1977, Viesturs made a pivotal decision that would shape his future. He headed toward Seattle, drawn by the towering peaks of the Cascade Mountains, including Washington’s Mount Rainier and Oregon’s Mount Hood.

The young man pursued his education seriously, earning degrees in zoology and veterinary medicine. He even worked briefly as a veterinarian, which he laughingly recalls as his “most normal 9-to-5 job.” But the mountains called to him stronger than any conventional career ever could.

The Journey Begins

Viesturs’s transformation from veterinarian to professional mountaineer wasn’t immediate, but once he committed to climbing, his dedication was absolute.

His first major breakthrough came in 1989 when he reached his first 8,000-meter summit at Kangchenjunga in Nepal, standing 28,169 feet above sea level. This achievement marked the beginning of what would become an 18-year journey.

The following year, in 1990, Viesturs successfully climbed Mount Everest for the first time, reaching the 29,035-foot summit. Then in 1992, he climbed K2, the world’s second-highest peak.

After these three incredible ascents of the world’s highest mountains, something clicked in Viesturs’s mind. “I’ve climbed the three highest peaks in the world, I love this, I think I have the skill to do more,” he thought. It was at this moment that he made a decision that would define the next two decades of his life: “Why not go out and climb the other 11? This would be an amazing journey.”

The Endeavor 8000 Project

What Viesturs christened “Endeavor 8000” was an ambitious personal quest to climb all fourteen of the world’s peaks above 8,000 meters without using supplemental oxygen. This wasn’t just about reaching summits; it was about pushing the absolute limits of human endurance and mental fortitude.

The challenge of climbing without bottled oxygen cannot be overstated. At altitudes above 25,000 feet, only an extremely conditioned athlete can survive, let alone climb.

Viesturs explains the grueling reality “That final climb from High Camp to the summit took about 12 hours. And for every step I took, I had to breathe 15 times. 15 times! And I had to get a pace going and a rhythm going saying that at that 15th breath, I have to take another step.”

For Viesturs, climbing without oxygen was about the pure challenge. “What it does is, in essence, it reduces the altitude of the mountain, it brings the altitude down to you just so you can go to the top. For me, that was a kind of a contrived way of gaining success, it was way more interesting to me to see if I could push myself physically and mentally to climb without oxygen. It’s just you, on the mountain, and that’s it.”

A Philosophy of Survival

Throughout his climbing career, Viesturs developed a philosophy that kept him alive when many others perished in the mountains.

His most famous motto became

“Climbing has to be a round trip – summiting is optional, but descending is mandatory.”

This wasn’t just a catchy phrase; it was a life-saving principle that he applied rigorously.

Viesturs recalls a perfect example of this philosophy in action. On his first trip to Everest in 1987, he was just 300 feet from the summit when conditions deteriorated.

Despite being so close to his goal after months of preparation, he made the difficult decision to turn back. “I was prepared to do that, and I was very proud afterwards saying, ‘Those are the rules that I learned, and those are the rules that I followed.’ Obviously I was disappointed that we didn’t go all the way to the summit, but it wasn’t our fault. If you don’t come home, it’s not worth it.”

This conservative approach to mountaineering set Viesturs apart in a sport where ambition often overcomes common sense. As he puts it: “The mountain decides whether you climb or not. The art of mountaineering is knowing when to go, when to stay, and when to retreat.”

The Mental and Physical Challenge

Viesturs understood that success in high-altitude mountaineering required both physical and mental strength working in perfect harmony. “I’d have to say both, because they go hand in hand,” he explains. “Clearly the physical demands are tremendous, you have to have strength, you have to have endurance. A lot of these expeditions can last for three months. And from the minute you set foot on that mountain, in many cases you’re not getting stronger, you’re actually slowly consuming yourself.”

The mental challenge was equally daunting. “When you go high especially without oxygen, the mental fortitude is huge because you’re pushing yourself to do something that your body doesn’t want to do. You’re suffering, you’re hurting, you’re climbing very, very slowly.”

To cope with these overwhelming challenges, Viesturs developed strategies for breaking down the enormous task into manageable pieces. “You have to break that huge day into something more tangible, saying, ‘I see that rock a hundred feet away, I’m going to climb to that rock. And when I get to that rock I’m going to find another smaller goal further.'”

The Dangerous Reality

Mountaineering at the highest levels is inherently dangerous, and Viesturs was acutely aware of this reality throughout his career. He survived the disastrous 1996 climbing season on Everest, when two close friends died, including Scott Fischer. The tragedy was later chronicled in Jon Krakauer’s bestseller “Into Thin Air.”

Viesturs felt closest to death during his 1992 climb of K2 with Fischer. At 25,000 feet, they were asked to help rescue a snow-blind and exhausted woman who had spent the night just below the summit. While tied together with a 50-foot rope, they nearly got swept off the face of the mountain. Viesturs, exceptionally strong at 5-foot-10½ and 165 pounds, managed to stop their fall with his ice ax after sliding 200 feet down the mountain.

Despite these close calls, Viesturs maintained an impressive safety record. “For whatever reason, I was always at the right place at the right time,” he reflects. “I have all my fingers and all my toes. None of my teammates were ever injured or killed. Is that luck or planning or being conservative?”

The Historic Achievement

Viesturs’s methodical approach to mountaineering paid off spectacularly. Over 18 years, he systematically conquered each of the fourteen 8,000-meter peaks.

His climbing resume reads like a who’s who of the world’s most dangerous mountains Kangchenjunga (1989), Everest (1990), K2 (1992), Lhotse (1994), Cho Oyu (1994), Makalu (1995), Gasherbrum II (1995), Gasherbrum I (1995), Broad Peak (1997), Manaslu (1999), Dhaulagiri (1999), Shishapangma (2001), Nanga Parbat (2003), and finally Annapurna (2005).

The completion of this quest came on May 12, 2005, when Viesturs reached the summit of Annapurna, one of the world’s most treacherous peaks. He had attempted Annapurna twice before, turning back in 2000 due to bad weather and in 2002 because of avalanches. When he finally succeeded, he became the first American and only the fifth person in history to climb all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen.

“When I came off Annapurna, which was my 14th summit, I was just absolutely elated,” Viesturs recalls. “Look at what I had just done, it took 18 years, I managed to do it, I financed it and I survived it.”

Life Beyond the Peaks

With his historic achievement complete, Viesturs made the difficult decision to retire from high-altitude mountaineering. The choice was influenced by his growing family responsibilities. He was married to Paula for 24 years and had three young children at the time of his retirement.

“At my age, I think I’m smarter than I’ve ever been,” said Viesturs, who was 46 at the time. “I’m maybe not quite as strong as I’ve been, but having the smarts and knowing how to function at high altitude compensates for that, and that’s important.”

His decision was reinforced when, just a week after his successful Annapurna climb, an Italian climber died on the very same route Viesturs had used. “Enough is enough,” he said at the time.

The Un-Retirement

Despite his firm declaration of retirement in 2005, the mountains proved too irresistible for Viesturs to stay away permanently. In 2009, he officially “un-retired” when he returned to Everest for the eleventh time as part of a team sponsored by Eddie Bauer, aiming for his seventh summit of the world’s highest peak.

The decision wasn’t easy, given that his wife Paula and three young children had grown accustomed to having him home safe during summit season. But when Peter Whittaker’s team came calling to test and publicize Eddie Bauer’s new “First Ascent” gear line, the pull of challenging himself in thin air proved irresistible.

Viesturs, who had once jokingly formed “Everest Anonymous” with some climbing friends due to his sworn-off attitude toward the overcrowded, commercialized mountain, found himself back on familiar terrain. He had left the door open “a small crack” to guiding on expeditions to big peaks he considered safer, and this opportunity fit that criteria.

His return showed he hadn’t lost many steps. During the expedition, he and Whittaker made the trip down from 21,200 feet to 17,500 feet in just 2½ hours. “The Khumbu icefall is a great motivator!” Viesturs wrote from base camp.

This comeback demonstrated that for someone like Viesturs, retirement from the mountains could never be absolute. The skills, experience, and passion that had carried him through his historic achievements remained as strong as ever

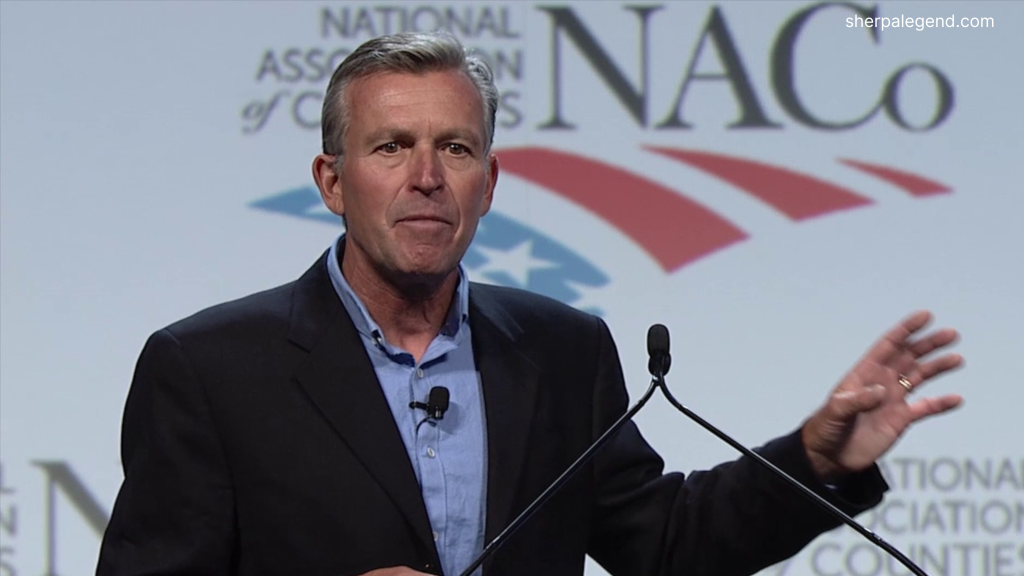

The Business of Inspiration

Viesturs successfully transitioned from mountaineering to motivational speaking, bringing the lessons learned in the mountains to corporate boardrooms. His experiences translated perfectly to business concepts: risk management, leadership, teamwork, overcoming obstacles, and decision-making under pressure.

“Teamwork is the same regardless of the enterprise,” Viesturs explains. “It is an implicit trust in, and recognition that the person next to you is No. 1. If we’re climbing a mountain together and you slip and fall, I’m there to save your life – the ultimate definition of teamwork.”

His success as a speaker led to engagements with major corporations and even sports teams. The Seattle Seahawks hired him to speak about teamwork before their 2005 season, and the team went on to play in the Super Bowl that year.

Author and Advocate

Viesturs channeled his experiences into writing, publishing several books including his bestselling autobiography “No Shortcuts To The Top” in 2005, followed by “K-2, Life and Death on the World’s Most Dangerous Mountain” in 2008, and “The Will to Climb: Obsession and Commitment and the Quest to Climb Annapurna – the World’s Deadliest Peak” in 2011.

Beyond his personal success, Viesturs became an advocate for Big City Mountaineers, an organization that helps under-resourced youth through wilderness mentoring experiences. He serves as spokesperson for their Summit For Someone benefit climb series, using his platform to help keep kids in school and away from violence and drugs.

Legacy and Recognition

Viesturs’s achievements earned him numerous accolades. In 2002, he received the historic Lowell Thomas Award from the Explorer’s Club, joining an elite group that includes Sir Edmund Hillary. In 1992, he received the American Alpine Club Sowles Award for his participation in two rescues on K2. National Geographic named him Adventurer of the Year in 2005.

Jim Whittaker, the first American to climb Everest, considers Viesturs “the best American mountain climber in history.” Yet Viesturs remains humble about his achievements, often deflecting praise and pointing to mentors like Reinhold Messner, the Italian climber who first completed all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks in 1986.

A Life Well Lived

Today, Viesturs continues to guide expeditions, including recent co-guiding of Mount Vinson expeditions with Garrett Madison and Aconcagua expeditions. He maintains his role as a Rolex ambassador and design consultant for outdoor equipment manufacturers. He lives in Ketchum, Idaho, with his family, and continues to climb Mount Rainier regularly, making his 216th ascent of the 14,410-foot peak in May 2021.

Looking back on his extraordinary journey, Viesturs offers this advice “I always tell young people to find a path in life that you can embrace and enjoy rather than something that you’re expected to do. That’s what makes life interesting.”

His philosophy extends beyond mountaineering: “Once you achieve a certain level of success, no matter where you are, what you’re doing, don’t be content with that level. Push yourself to another level. People that are successful are always pushing.”

For Viesturs, the mountains were never just about conquest; they were about personal growth, facing fears, and discovering what was possible. “If you can look back and say I lived my dream,” he reflects, “that’s a life well lived.”

Ed Viesturs proved that with patience, preparation, and respect for the mountains, even the most impossible dreams can become reality. His legacy stands not just in the record books, but in the lives he’s inspired to reach for their own impossible heights.